Before his death sparked a public debate about the state of China’s health care system, 21-year-old student and cancer patient Wei Zexi would often log on to question-and-answer website Zhihu to share his experiences. In one post, he talks about medication from India, and how without it he “would have already died from not being able to afford drugs.”

Like Wei, many Chinese patients look to countries like India to find the drugs they desperately need but that are either unaffordable or unavailable in their own country.

For one group of patients, those with the potentially chronic and life-threatening liver disease hepatitis C, a whole industry has sprung up surrounding their pursuit of a new miracle drug that is not yet available on the Chinese market.

A combination of the chemicals ledipasvir and sofosbuvir, the drug comes with the promise of reduced pain at relatively lower cost. It’s an appealing proposition for people such as Xie Heying, a 63-year-old retired school teacher. In 2009 Xie was diagnosed with hepatitis C, a liver disease transmitted by blood or body fluids. Xie is not sure how she ended up with hepatitis C, but she suspects it was from a blood transfusion.

Diagnoses of the liver disease are on the rise in China. Newly reported cases of hepatitis C rose to 232,400 in 2015 from 202,803 in 2014 — a 15 percent increase, according to China’s National Health and Family Planning Commission (NHFPC). The overall number of hepatitis patients in the country is estimated at over 10 million, with the majority being undiagnosed, according to the commission.

The only treatment available in China is a weekly regimen of interferons, or proteins that boost the body’s immune system, and antiviral drugs, which must be administered together over a period of up to 48 weeks. This treatment is expensive and ineffective, and it often has serious side effects, including anemia. Since Xie has had a low red blood cell count since 1986, she feared the treatment would be fatal in her case, so she looked for an alternative. She soon discovered that other treatments were available abroad.

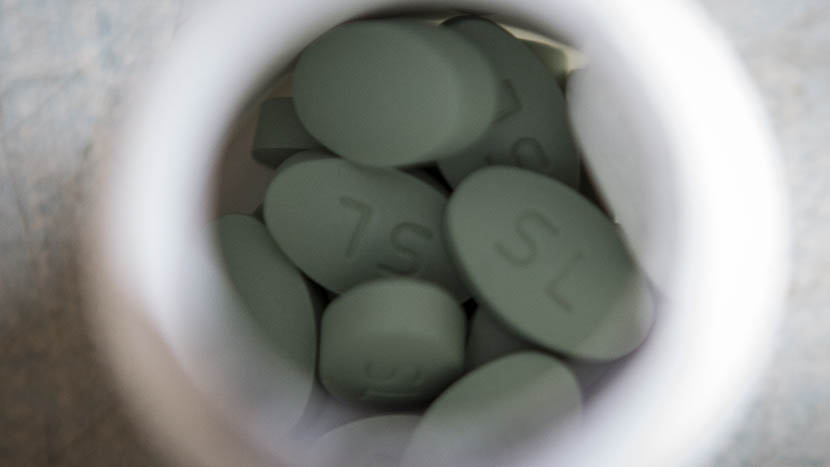

“I spent the last six years waiting for this medicine,” Xie says, seated in her living room in her home in Zhenjiang, Jiangsu province. She is staring at a small cardboard package. Despite its modest size, the package holds life-saving tablets.

The ledipasvir-sofosbuvir medicine Xie Heying bought in India. Zhenjiang, Jiangsu province, Jan. 26, 2016. Yang Shenlai/Sixth Tone

With license from U.S.-based Gilead Sciences, Indian pharmaceutical companies produce generic forms of the ledipasvir-sofosbuvir drug and market them in more than 100 countries — but not in China. In contrast with the treatment available in China, the Indian medicine offers, in most cases, a quick cure with relatively minor side effects, and for nearly half the price.

In order to get her hands on the drugs, Xie traveled to India in January. She did so as part of a group tour organized by Bluehealthcare Overseas Medical Consultation, a Chinese agency specializing in medical trips. From January to mid-March 2016, the company helped 11 Chinese patients like Xie travel to Delhi, the capital of India. The patients spend three or four days there to undergo blood tests and other examinations. Then they buy the drugs and finish the 12-week treatment at home.

Shanghai Kedi Healthcare Management & Consulting was one of the first companies in China to help hepatitis C patients travel to India for treatment. The company’s first medical trip took place in June 2015, according to Dr. Zhao Xinhao, who is in charge of project development at Kedi. “In the beginning, we sent two to three patients in a single tour,” Dr. Zhao said. “That number has now grown to 20 patients.” As of mid-March, the company had helped more than 300 patients get treatment in India.

From the beginning of 2015 to March 2016, Chinese patients traveling to India, Laos, and Bangladesh for relief from the liver disease numbered around 1,000, according to Xu Jun, head of the medicine evaluation division at Beijing-based Pharmacodia Information Technology, which offers big-data information solutions for medical research and development in China. For years, Xu has been studying the global progress of research and development of hepatitis C drugs. He predicts as many as half a million Chinese patients could be making similar trips in the years to come.

Besides availability of new treatments, cost is another factor in attracting Chinese patients to India. In China, the total cost of hepatitis C treatment varies between 50,000 yuan and 70,000 yuan ($7,700 to $10,800), or up to double the cost of going to India to buy the medication.

In the U.S. Gilead Sciences markets its hepatitis C drug as Sovaldi, which contains only sofosbuvir, and Harvoni, which contains both ledipasvir and sofosbuvir. In an email response to questions from Sixth Tone, Gilead Sciences said that while the drugs had not yet been approved for general use, the China Food and Drug Administration had nevertheless approved clinical trials for both. The Sovaldi study, approved in January 2015, is ongoing; the Harvoni study, approved in January 2016, will begin later this year, the company said.

Gilead Sciences declined to comment on when the company expected drugs would be available on the Chinese market, citing that the trials have not yet been completed.

Xie’s daughter had wanted to buy the drugs for her mom when she was studying in the U.S., but she gave up after learning the cost. “In the U.S. the drugs were priced at about $1,000 a tablet,” Xie said. The generic drugs she bought in India, however, cost 25,000 Indian rupees ($380) for an entire box of 28 tablets.

Zeng Zhiqiang, a 37-year-old self-employed businessman, is now completely cured of hepatitis C. Zeng said he didn’t want to undergo the conventional treatment in China, citing the side effects and low cure rate. He looked at a few countries before deciding to go to India for treatment. In the case of Japan, he discovered treatment with ledipasvir and sofosbuvir would cost about 300,000 yuan. Finally, Zeng flew to India in July 2015 with the help of Kedi, spending just 38,000 yuan.

The issue of Chinese citizens obtaining new drugs from foreign companies appears to have raised concerns from the Chinese government. Ma Xiaowei, deputy head of NHFPC, said at a press conference in March that the commission was considering opening a new “green channel” for certain medicines that would result in speedier access to the Chinese market.

Many patients, however, are not willing to wait. Before hearing about the generic Indian drugs, Xie had never thought of visiting the South Asian country. After Xie’s son found out about the organized tours in December of last year, he footed the 35,000-yuan bill for his mom.

Despite the prospect of finally getting the medicine she needed, Xie was not overly enthusiastic about her upcoming visit to India. She had heard bad stories about how the country was disorderly and dirty. Her son also urged her to be careful.

Most Chinese hepatitis C patients are apprehensive about going on medical trips to India, Dr. Zhao said, adding: “Chinese people don’t have sufficient understanding of the medical system and hospital conditions in India. They don’t realize there is a highly developed manufacturing industry for generic drugs. Some patients were worried that they would get swindled upon arrival in India.”

One member of the medical tourist group receive a blood test at a private clinic in Delhi, India, Jan. 11, 2016. Courtesy of Xie Heying

Even after their arrival in India, Xie and the other patients were unconvinced. All the patients in Xie’s group, herself included, refused to undergo a gastroscopy examination at a private clinic in Delhi, fearing it was unhygienic.

On the third day of the trip, the travel agency informed the patients that it would buy the medication for them. The patients insisted they would go to the pharmacy themselves. “We couldn’t stand waiting in the hotel for the precious drug anymore,” Xie said. After returning to the hotel with three boxes of pills in hand, Xie played cards with the other patients that evening. “We just burst into laughter,” she said. “That evening I slept more soundly than I ever had in India.”

Since her trip, Xie has changed her views about India. “After I am free of hepatitis, I’d like to travel to India again, this time as a tourist,” she said.

(Header image: Xie Heying shows a box of pills she bought in India. Zhenjiang, Jiangsu province, Jan. 26, 2016. Yang Shenlai/Sixth Tone)

原文链接:https://www.sixthtone.com/news/china-looks-india-health-and-hope#

(责任编辑:康安途海外医疗)